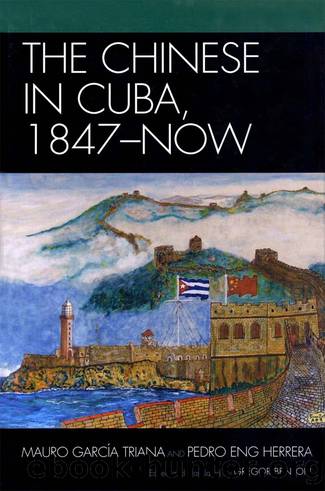

The Chinese in Cuba, 1847-Now by Benton Gregor;García Triana Mauro;Eng Herrera Pedro; & Pedro Eng Herrera

Author:Benton, Gregor;García Triana, Mauro;Eng Herrera, Pedro; & Pedro Eng Herrera

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780739133453

Publisher: Lexington Books/Fortress Academic

Published: 2016-03-31T00:00:00+00:00

As for the Chinese surrounding the merchant, Meza describes them as âspitting out the smoke they extract from their long pipes filled with snuff dusted with opium to improve its flavor.â35

Later, probably at the start of the twentieth century, an anonymous author wrote El chinito de la suerte (The lucky little Chinese), a stage comedy. The Chinese Antonio had disappeared. His wife Petra and neighbors were looking everywhere for him. News spread of a ghost that appeared in the district on certain nights, which people thought was the ghost of the supposedly murdered Chinese. The wife could not explain his disappearance, which became the subject of conjecture. The police made enquiries, but could not find out what had happened. Tired of searching, the police chief grabbed a Chinese, perhaps thinking it was the missing man or even the ghost. He summoned the neighborhood and brought Achón before the crowd. Achón took out a list of charada china and declared: âPlease donât arrest me, Captain. Iâm not a murderer, I just play the charada china.â The policeman asked Petra if he was her husband. She seems doubtful: âNo, but he looks the same.â At that very moment, a postman bursts in with a telegram for Petra. Everyone wants to know its contents. She reads it out: âI won the lottery, leaving for Canton to join my wife. Antonio.â âMy God, I am abandoned!â All are aghast. The women become indignant. Commentaries and exclamations ensue. The police feel released of responsibility after their hard search.

Ana, a neighbor, asks, âDid he not die?â Achón answers with a Chinese bright idea: âYes, he died. A Chinese who dies here has to go to Canton.â A policeman: âWeâve messed things up.â Another: âBoss, in that case Iâm returning to Havana.â Another: âGumersinda, letâs get married and Iâll retire from the police.â Another: âMariana, if you give me Cucaâs hand, I guess youâll be grandparents within the year.â Achón speaks again, this time with grace and daring, to Petra: âGirl, you want to swap, Chinese for a Chinese?â Petra, between tears and smiles: âOK, come over here.â Ãico: âOK, gentlemen, letâs celebrate the conclusion of a mysterious crime.â Another policeman: âIf it turns out to be true, heâll end up on the garrotte.â36

In his novel Juan Criollo (John Creole), Carlos Loveira Chirino (1882â1928) writes about a Chinese sweet vendor. The description is racist: the Chinese is said to be dirty. The vendor is assaulted by a gang of thirteen-year olds who steal his merchandise. Later, one of the boys takes pity on the Chinese, but the gang leader tells him not to be sentimental: âFuck him! Why is he Chinese?â37

Lino Novas Calvo (1903â1983) also dealt with Chinese themes. In his Luna nona (Ninth moon), he told a story about Chinese lanterns and kites in a Cuban town. In another story, Aquella noche salieron los muertos (That night the dead came out), he described a strange situation in a sugar mill community where a bandit and his Chinese henchman commit various crimes.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Vikings: Conquering England, France, and Ireland by Wernick Robert(79224)

Ali Pasha, Lion of Ioannina by Eugenia Russell & Eugenia Russell(39942)

The Vikings: Discoverers of a New World by Wernick Robert(36831)

The Conquerors (The Winning of America Series Book 3) by Eckert Allan W(36716)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32094)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31482)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31436)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22780)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18341)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18269)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(14804)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14006)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(13828)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(12916)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(12880)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(12834)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(11857)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11843)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(11652)